Conversations with the readers about what technology is and what it may mean to them. Helping people who are not technically oriented to understand the technical world. Finally, an attempt to facilitate general communication.

Saturday, January 27, 2018

What is Net Neutrality? Why should anyone care?

First thing to mention -- net neutrality does NOT guarantee that you have equal ease of access to all websites nor that you can transmit to, or download from, a particular site just as fast as all other sites. The speed of a connection, and the ability to access a site, depends on many different factors (including, but not limited to, net neutrality).

The current primary differences occur at the physical site of a website. What kinds of hardware do they have? What types of software (and how up-to-date) are they running on their servers (the computers that host the website)? What is the bandwidth of the website's connection to the rest of the Internet? Consider the bandwidth to be equivalent to the diameter of a water pipe -- it limits how much data can be transmitted. The transmission medium will determine the speed.

We are now at the border of the "cloud" of the Internet. Once upon a time, there was still a lot of unpredictability once data had reached what we now call the Internet (or, at that time, the various Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) protocols such as TCP/IP, supporting the DARPAnet) because the connectivity was neither available all of the time nor did each connection (or "hop") have the same speed and bandwidth. If your data went via one path it was pretty quick. If it went by another path it might take hours.

By the time of the transition to what we think of as the Internet had taken place (marked by use of the first freely available browser, "Mosaic", more than anything else), there were still differences in the speed of different data paths through the network. However, we are talking about an overall speed that would now be considered unusable. Within this very slow network, the differences between different data paths were not as noticeable.

Fast forward to the Internet of today and the data access from home or business into the Internet and out to the website's server is largely taken care of by a homogeneous set of connections provided by your Internet Service Provider (ISP). There are common, "backbone", data paths that may be used by multiple ISPs -- but you largely get the bandwidth (total amount of data) and speed that you pay for from your ISP.

And that is at the heart of the issue of Net Neutrality. Right now, you pay for a certain amount of data and a certain access speed (possibly different for each direction). But, the ISP is neutral to the contents of the data and the destinations of each transfer of data (with the exception of potentially examining the data streams for viruses and other hazardous information). Whether you are streaming a movie from Netflix™ or accessing the on-line catalog of the Library of Congress, you will get the same service (up to the access point of the website).

Elimination of net neutrality means that it CAN matter just what data you want to access and from where you want to access it. There are two categories of how this can affect the general consumer. The first is primarily a business purpose from the ISP -- to increase profits from their services. If you just use the Internet to access mail, then there may be one service level. If you use social media, that may be another service level (for more money). If you stream movies on a regular basis then that could be yet another service level. In addition, if the ISP had a working partnership with a streaming company (or was owned by, or owned, it), then access to streaming service A might have a higher fee than for access to streaming service B (from which they already directly leverage profits).

In this first category, the general intent of removal of net neutrality is to increase profits. Some people might pay less for low-end access and service. Others will pay more. The net effect is expected to be an increase in profits -- the concept of removal of net neutrality is NOT "revenue neutral". If it were, the ISPs would not care -- net neutrality is actually easier for them.

The second category is one that is often considered to be "something that cannot happen here" (but it certainly happens in countries that do not have a policy of net neutrality). If you are treating different data and different destinations differently, this is just another way to define censorship. While it may not occur, it is very hard to prove just what is happening once net neutrality is removed. Did a website "fall between the cracks" or was it deliberately made slow, and difficult (or impossible), to access? Is it coincidental that the political leanings of the website are counter to the desires of the owner(s) of the ISP? How is a small website going to enforce First Amendment (in the U.S.) rights? Can they? Can the Net still be regulated?

Sunday, January 21, 2018

Income Inequality: How does it create a tightening spiral?

With the new tax "reform" in the United States in the news, the topic of income inequality resurfaces as something of interest. As will have been noticed, the way that the economy actually works is something that I find continuously fascinating. As for income inequality, just what is it? How does it begin? How does it accelerate or become less?

[Please note that the numbers used within this blog are snapshots and may be different in a different year's snapshot.]

In the first place, there are two different inequalities within a capitalistic economy -- income inequality and wealth inequality. These are often discussed as if they were the same thing. While it is true that there is often a correlation they are not the same. Income inequality is the difference in the amount of usable income in a given period (usually a year) between different income divisions (see my blog about income groups if you are interested). Wealth inequality is the total control of capital associated with a particular division. Generally, wealth inequality is even worse than income inequality because wealth both accumulates and compounds (wealth generates more wealth).

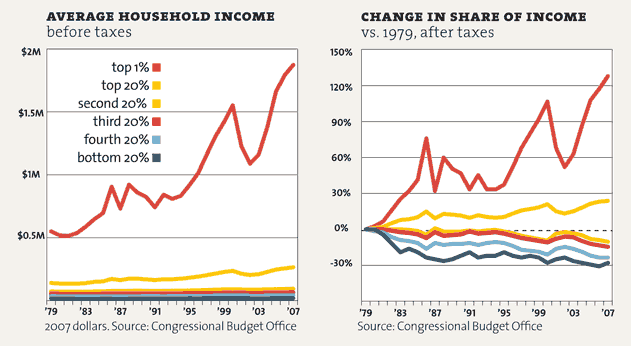

If we look at the following graph of income inequality in the United States:

First note that these graphs only continue up until 2007. The general trends have continued through the present year. Next, note that the increase is much higher with the top 1% than the next 19%. The bottom 80% actually indicate a DECREASE in income.

Income inequality arises out of the difference between income and required outgo. For the lowest income groups, the amount of income is less than the required spending. This deficit is dealt with by supplements from the general tax pool and by dropping budget items that are not immediate for the family -- dental care, general medical care, and so forth. Eventually income rises to the point where the income matches what is required for spending for essentials.

We have now reached the bottom of "middle income". This continues until there is extra income beyond essentials. This is the point at which there is actually a voluntary potential of the family being able to accumulate additional wealth. In other words, there is an amount of money that has discretionary spending possible. It could be put into savings, or invested in stocks and bonds -- or it can be spent on more expensive cars, long vacations, fancy clothes, and so forth. In the first situation, the family has the potential of raising their overall wealth (and income). This is the historic "rags to riches" story -- but it requires having enough income to have excess and the number of people in this category continues to shrink and, for better or worse, an expensive car often wins out over extra savings.

Finally, we hit that upper income category. This is where both survival and initial spendable extra income have been exceeded. It has to be either hoarded or invested. This is complete "gravy" and has nothing to be done with except to expand it. This is where the tax laws can be written to help the vast majority who generate the income or to help those who already have more than they need.

There is no "trickle down" -- no lower levels that make 1/4 or 1/3 of what the higher level employer makes (and then continuing on down with the next level making, perhaps, 1/8 or 1/6 of the highest level). Only a "splash over" occurs -- lots of service people employed to do things that those with excess income do not want to do themselves. (Of course, the service people are still grateful to have income.)

So there is the summary. Those who don't have enough to survive and must be helped, those who do have enough to survive but are faced with choices on spending and often spend the additional income beyond survival, and the third category with excess that has no choice but to keep growing unless compensated for with tax laws that re-distribute the money back to the people who generate it.

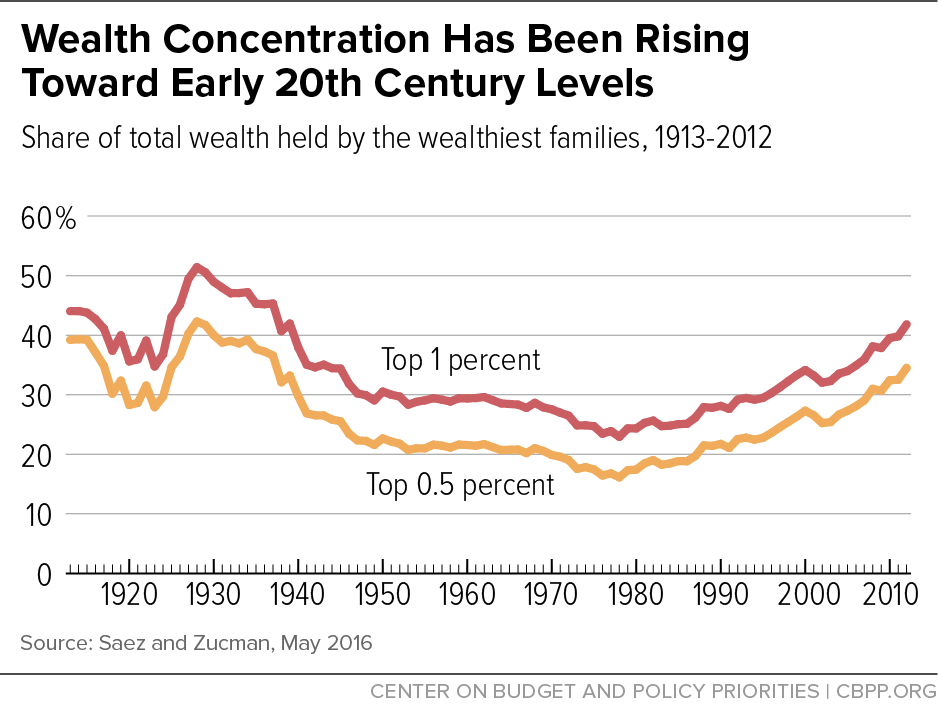

Beyond fairness, however, there are reasons why it is very dangerous to allow working capital to be concentrated in the hands of a small percentage. First, the rich are not particularly different from the poor (except where nutritional situations have caused permanent damage) -- they have a "normal" distribution of intelligence from not very to average to very smart. If the top 0.1% of the population (about 160,000 families in 2015) families in the United States have control of 22% of the nation's wealth (2015 statistics) -- that means that 80,000 families of below average intelligence are controlling 11% of the nation's wealth. Even more, the top 10% (16 million families) control 78% of the nation's wealth -- giving us 8 million families of below average intelligence controlling 39% of the nation's wealth. In other words, there is a lot of economic power concentrated in the hands of people who have no particular special quality about knowing how to make use of it.

The second part of the danger is that, with 16 million families (out of approx. 160 million) controlling 78% of the nation's wealth, we have a situation of a capital circulation problem. If 160 million have the capacity to equally spend on goods and services, the capital flows freely. If it is concentrated in the hands of a few, it is more parallel to a tourniquet being applied to part of the body.

We have a continued concentration of wealth in the hands of a few and the recent tax "reform" act will accelerate this concentration. We have two major demonstrations of this situation (I do not claim ONLY two demonstrations) -- the Great Depression and the French Revolution. Both were situations where income got overly concentrated in the hands of the wealthy.

We have now surpassed the point in history of the end of the 1920s and are rapidly heading to the point in 1929 where someone, who had a lot of capital and power in his (or her) hands made a mistake and started the dominos falling.

Will this happen again? I don't know but we have few documented cases where income concentration exceeded these levels and a stable society continued. These cases were demonstrated primarily in pre-colonial Europe and an outlet existed (unfortunately for the existing native populations of Australia and the Americas) for the poor and desperate. Where is that outlet -- that safety valve -- now?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

TAXES: Progressive versus Regressive versus Flat; among other matters

“The only things certain are death and taxes”. Just what are taxes and why are they present everywhere? As I wrote about in 2014, money...

-

Life is change. It can be slow, fast, or abrupt — but it happens. Our planet has gone through changes throughout its history. Asteroids...

-

Everyone knows what a criminal is, don’t they? They’re the ones that rob or break things or get into fights. All of those things can ha...

-

This newsletter/blog is unusual for me. I am extremely grateful that I have no direct experience about the subject matter — recidivism....