Investing in real estate is not always a sure bet -- the "bubble" in the U.S. in 2008 is a recent indication of a "correction" when real estate prices were rising much faster than demand would normally expect -- and when people were going beyond the point where they could truly afford to buy real estate. But, in general, real estate prices continue to rise.

This is something very pleasant for the real estate owner. Over the long run, the value of the land or property (a "parcel") is expected to rise. In the short run, it may be difficult to sell. It is not "liquid" -- it can only be exchanged for money or other value if someone else happens to want it. But, if it is a good piece of land or property, it will probably find a buyer at a good price.

What defines a "good price"? What are the components of the rise in value of land or property? Realtors are likely to say the phrase "location, location, location". That is actually only half of the criterion -- the other half is "distinctive". By building high or covering a wide area, the specific location can be widened and a specific property or land area becomes less valuable. However, with increasing density and encroaching natural borders (such as hillsides or rivers) or supportive resources (water, power, sewage, ...), there is a limit to the number of parcels that can be available at the same approximate location. Each, of course, will have their own view and orientation which may make them more, or less, valuable.

Another component of the price can be quality. A well-built, or designed, home should be of greater price. If the person/company that designed, or built, it is well known (Frank Lloyd Wright?) then that automatically adds to the price. History can add to the price -- if Abraham Lincoln slept there then the price should go up (assuming it can be proven).

Yet another aspect of pricing is determined by the general income level of the neighborhood. There will be a lower limit of reasonable pricing determined by the cost of materials (not applicable in the case of land) and local labor -- but that lower price limit may be voided in cases of desperation or foreclosure. However, the price will float upwards as the prices of the parcels around are rising (for whatever reason) as competition between realtors, owners, and buyers start to change the lack of sufficient property into higher prices

All of these parts of determining value are indicative of why housing prices vary -- more expensive in some locations and less expensive in other areas. A 2,000 square foot house in San Jose, California will cost a lot more than a 2,000 square foot house in Mobile, Alabama. (Even though the quality of the house will probably be less in San Jose.) Within Wichita, Kansas, a 2,000 square foot house in a wealthy neighborhood will cost more than that within a lower income neighborhood (although neither will come close to the price of a house in San Jose).

Once upon a time (when I was growing up -- not quite the dark ages), my architectural drafting instructor told us about an expected ratio of land to square footage of a house. As I recall, the "footprint" (the amount of land the foundation required) of a house was supposed to be no more than 1/9 of the lot size (land). (It was never indicated as to any rule-of-thumb on apartments or townhouses.) With a reduced expectation, and use, of land -- as well as an increased percentage of the total price spent on land -- it is now not unusual to have a house occupy 1/3 of the lot (sometimes even less in urban areas).

In addition to the house occupying more of the lot, there is incentive for the builder to increase the size of the actual house. Houses are listed, and compared, by $xxxx/square foot (in other areas Money/square meter). The price to build is NOT the same for all sections of a house. Kitchens and restrooms are more expensive. By adding more square footage to the "living" areas, builders can squeeze out more profit without increasing the price per square unit of area.

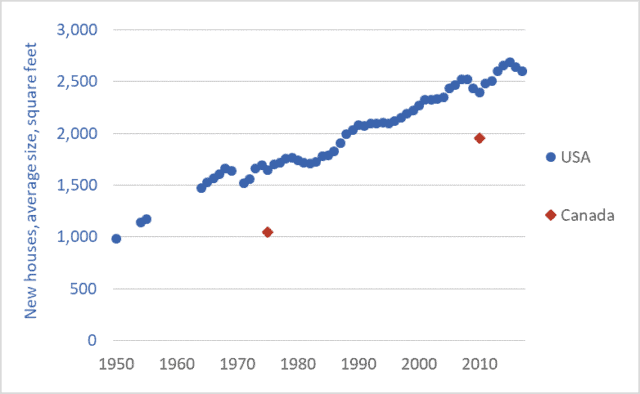

A chart of this increase in house size can be seen from Darrin Qualman's post.

Perhaps this is not particularly egalitarian -- people who have more income (or more inherited wealth) can buy larger houses in more desirable locations with better views, schools, climates, landscaping, local attractions and such than those who are poorer. But such has been the case since land and property started "belonging" to people and is likely to continue.

The greater problem is having the AVERAGE housing price go up faster than the AVERAGE wage. As time goes on, a smaller and smaller percentage of the population can afford to buy housing. This also reflects upon the situation for renting since renting is the process of fostering out to others property that has been purchased by someone. In other words, rents are loosely based on the amounts of mortgages for the property.

Before I started researching to double-check facts for this blog, I thought that real estate prices were rising much faster than inflation. It does not appear to be the case. Even wages are reasonably stagnant (decreasing only a small amount, on average, against inflation) from amhill.net's post (you may find other sections of the post of interest, also).

But, since house prices are per square foot and the average size of a newly built house has increased by 250%, many fewer people can afford a house. What they can afford is an apartment (or maybe a townhouse) which shifts the size back to that of a house built in the 1950s. That may not be that unreasonable -- the increased size is a factor of literal "inflation" but it does mean that the "American dream" of a stand-alone house with its own yard is more and more out of reach for many people.

One new trend against this flow is for that of the "tiny house" movement. Note that, although the square footage is quite a bit smaller than the typical newly built house of current days, the price per square unit of area actually goes up (once again, the cost of kitchen/bathroom is more expensive and there is less "living area" to offset that cost). Of course, people can still buy their own lots and have their own "moderate house" built. It just doesn't seem to be currently popular -- which means that it may prove hard to sell in the future.

In summary, part of the lack of ability for people to afford housing is an illusion. Since the size of houses has increased (and the prices accordingly) and wages have remained stagnant then fewer people can buy the houses currently being built. However, if the size of the living area is kept constant -- and the form of the living space is allowed to change from that of a "dream house and yard" -- then people's ability to afford housing has not changed. Unfortunately, the numbers of housing units built of an affordable size is not keeping pace with the percentages who can afford them -- causing housing and rental shortages.