Conversations with the readers about what technology is and what it may mean to them. Helping people who are not technically oriented to understand the technical world. Finally, an attempt to facilitate general communication.

Saturday, December 8, 2018

The poor are from Earth; the born rich are from Jupiter

Once upon a time (now over 25 years ago), John Gray wrote a book called "Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus". The primary precept was that most men have very different communication styles, history/usage of words, emotional needs, and modes of behavior from that of most women. Of course, the book was only an abridged version -- the full explanation of such is actually a multi-volume series that competes in length with, or exceeds, a set of the old Encyclopedia Britannica and goes out-of-date within weeks.

Similar to George Washington's "cherry tree", it is highly unlikely that Marie Antoinette ever said "let them eat cake". But the concept that people might not have enough to eat was incomprehensible to her. Food had always just appeared (it was never visibly raised, purchased, transported, or prepared) for her. From the viewpoint of the poor, they felt they were being mocked and could not conceive of anyone being unaware of the pain, and work, needed for daily survival.

Such a clash brought about the French Revolution and earnest use of the guillotine. The disjoint environments of the lowest class from the higher classes in Russia brought about the Bolshevik Revolution (followed by the Communist Revolution). In the United States, being a division of income rather than social class, it brought about the Great Depression.

In an explicit class system (such as Britain, or India, or many other areas) each social class is clearly trained in expectation of their eventual roles. Certain language, and usage, is taught from an early age. Clothing has its clear do's and don'ts and has its own (usually unwritten -- but passed along from generation to generation) appropriateness depending on the situation. Most important, accepted behavior within the social class, as well as accepted behavior between levels of the social classes, are firmly indoctrinated. These social class behaviors and expectations are not directly associated with wealth but the lack of sufficient money can sometimes cause situations where it is difficult to properly meet the expectations of the social class.

Movement between social class levels is very difficult. There is certainly a lot of explicit exclusion ("you cannot interact with them") but much of it is a severe discomfort which results from not having been raised from birth into the sub-societal expectations. Always a "fish out of water" and never fully accepted.

In the case of income classes, movement is possible -- although presently becoming more and more difficult. Once again, however, if a person has never been an active part of an income class, it is a different world for them. We have heard millionaire politicians make statements very parallel to the mythical "let them eat cake" (in particular, not knowing how much a gallon of milk costs, the cost of rent in a local city, or how living costs are paid).

If you have never been involuntarily hungry and have never worried about whether there will be food to eat then it is not a concept that is easily understood. If health care has been always available and never questioned then the idea of others not having health care is not understood. In even more severe form, if one has never even wondered how they have food, clothing, vacations, houses, and so forth then the innate assumption is that is true for everyone. Not only is it difficult them to understand -- but many fall back into the false assumption that "it must be their fault".

Note that people who HAVE moved between income classes ("rags to riches" or "lost everything") can have a direct understanding of those income classes that they have been an active part of. People BORN within an income class have to deliberately self-educate (being part of the Peace Corps for a couple of years might help a lot for the wealthy to have some relevant experience) to understand other income classes.

In the case of democratically elected governmental representatives, it is important to bypass the advertising, and campaign snapshots, and remember that they are there to REPRESENT you -- born millionaires (or born billionaires) will be severely crippled in the ability to understand, and represent, the general non-wealthy masses. Allowing non-representative people to represent the voters is a CHOICE and must be remembered as such. If you want your representatives to represent you, then you must choose people who understand, and have experienced, the problems that they need to address.

Monday, November 19, 2018

Competition -- the good, bad, and the ugly

Competition exists in all aspects of our lives. Sometimes it is not obvious -- which apple looks the best to eat? Do I like the green shirt or the red one? What is my favorite subject in school? Choices involve competition even if the things among which one must choose are not actively competing against each other. In these cases, the choice is usually made by our subconscious acting from our personal histories.

Competition can be eliminated via monopolies -- either regulated or unregulated. An unregulated monopoly is the only source and it can disperse it's products in any way, and at any price, at any usable quality. A regulated monopoly provides the only source but there are outside agencies that determine the parameters of its ability to sell -- quality, price, availability.

Even if there are two or more sources for a product, competition can be avoided if the sources make agreements between themselves about conditions of each of their production and distribution. Splitting the market, agreeing on certain lower limits on price, active sharing of research, and so forth can give an appearance of competition while the reality is just that the market is shared to enable all sources to maximize their profits.

If a product is not wanted, there can be no competition. Of course, most new products start as an unwanted entity in a condition of unregulated monopoly. They now have to persuade people that they want or need the product. This establishes the market and the introducing source can take advantage of their situation to establish their association with the product. Once the market has been established, then competition will appear (unless squashed by the introducing, or largest, company -- suppressing competition legally or illegally).

Each source for a competing product (and the product can be merchandise, services, political candidates, locations, or any other item from which one must make a choice) wants to persuade the buyer that they have the "best" product. Advertising and marketing attempt to create a specific positive perception -- which may, or may not, be in agreement with measurable, and verifiable, qualities.

The grand prize for an advertising/marketing division is to establish a brand such that people will choose according to the brand and only minimally (or not at all) evaluate the qualities of the products. On the scales of evaluation, a positive brand image is a heavy weight on the side of choosing that sources products. This can be reasonable, as brands are established by satisfying people with products on a consistent basis. However, if the brand becomes the only criterion, there is no longer any need of any positive qualities. Eventually, a product that has only brand recognition and is a poor product will lose its brand reputation and effectively have to start over within the market.

During the phase of true competition (no brand loyalty, no monopolies, required by the consumers) between two or more sources, competition can achieve continuous improvement of the products. One source "wins" and the other examines the reasons and improves their product to the point where they start "winning" and then the OTHER source starts improving their product. Once again, this can apply to many different products -- social and business. So, during this phase, there may be a "lesser evil" or "less bad" but making a choice towards that direction still continuously improves the choices from all sources.

Saturday, October 6, 2018

"Normalizing" -- when the abnormal is ignored to emphasize the rest

"Normalization" is spoken of quite a lot these days -- primarily by those criticizing the traditional media. But just what is normalization? Well, not too surprisingly, it is the process of ignoring parts of a person or a situation that would NOT meet the description considered "normal" and emphasizing (usually quite out of proportion to the abnormal portion of the situation or person) what is expected -- or "normal". Distortion of reality -- whether to make it appear "normal" or to make it appear "dangerous" or "oppositional" -- is very dangerous because the reactions that might make sense, if it was real, are normally inappropriate and counter-productive for a distorted reality.

As an instance of description, attributes of a leader might include diplomatic, patient, assertive, charismatic, hard-working, reliable, moral, stable, competent, mature, respectful, logical, eloquent, honest, responsible, sharing of credit, ... It is rare for a leader to have ALL such desired characterizations but -- if someone in the position of leadership has only one or two of these attributes and these are emphasized while the others that they don't have are ignored -- that is "normalization".

The following are a couple of historical examples of the general scenarios where normalization took place. In the first, there is an attempt to make someone, or something, which is quite abnormal seem normal by ignoring that which is not desired. In the second, the abnormal is not ignored but it is ridiculed and minimized (it will become obvious to everyone so it's not something about which to worry). There is a third type where the normalization is used to squeeze someone, or something, back into a stereotype when the story, fully described, actually contradicts the stereotype; going into such an example requires a lot of back-story and, perhaps, might be done in a future blog.

One example from history of the first category concerns that of Benito Mussolini. In 1922, with 30,000 of his "blackshirts", he marched into Rome and declared himself "leader for life" -- that is, totalitarian dictator. He was the leader of the Fascist movement at that time. The press (mostly printed newspapers -- some radio) of the time mostly gave him either neutral or mildly positive coverage. Why? There were two significant factors -- one was that Italy, relatively newly coalesced into a single country, was in turmoil and undergoing both economic and infrastructure chaos. The other is that the U.S., and much of western Europe, was in the midst of the unregulated ultra-capitalism phase which led to the Great Depression. Strong, enforced, control of a chaotic populace seemed to be a generally beneficial thing.

Yet, there were many parts to both Mussolini's personality and political behavior which were strongly against the declared values of the U.S. and western Europe. He strictly controlled the press and dealt severely with any criticism of himself or his actions. He did what he wanted without regard to any existing written, or common, law and often used violent means to eliminate (murder) anyone in direct opposition.These aspects of his rule were rarely reported (Ernest Hemingway and The New Yorker were a couple of exceptions). By leaving these out, Mussolini was presented as a "normal" leader.

Mussolini's contemporary -- and part of the World War II "Axis" -- was Adolph Hitler. His treatment by the media was somewhat different from the positive slant given Mussolini, and is closer to the second form of "normalization". Hitler was able to have some of the positive reactions adhere to him as the "German Mussolini" as he was portrayed as being with him and like him.

However, his actions were so outrageous that the media literally refused to believe them. In addition, they were faced with a situation of a choice between self-censorship and not being able to report at all. This leads to a very important, and difficult, question -- which is more useful -- having to report things that are known to be false or not being able to report at all?

Finally, they kept assuming that the people of Germany would "soon" recognize what an outrageous monster that he was -- but by that time, his control was so firm that anyone who objected to him or his actions was promptly shot or sent to the concentration camps. The majority of Germans was willing to just do whatever they needed to do to survive.

They had moved past the point where the general citizenry could easily stop him -- they had probably passed that point in 1933 when Germany's equivalent of the U.S. Congress -- the Reichstag -- gave Hitler unlimited "emergency" powers to bypass the law via the "Enabling Act". Before that, they could have voted out the Nazi party and restored democracy. Instead, we had World War II and casualties of 50 to 80 million people.

Saturday, September 29, 2018

Those butterfly wings must get tired -- initial conditions and small things matter

Back in the Dark Ages (pre-WWW), in 1987, James Gleick had a book, Chaos: The Making of a New Science, published. In this book, he introduced people to something called "chaos theory". If you want to know specifically what that entails, you should read the book as I am not qualified to paraphrase it. However, one of the examples in the book (which became rather famous and also associated with various jokes) was that the flapping of a butterfly's wings in one remote region (let's say the Andes Mountains in Peru) may cause a thunderstorm somewhere else (maybe in Texas in the U.S) (that is NOT an exact quote).

The conclusion that I drew from the book is that it is impossible to know, in advance, whether something is important or not, or how important it is, until much later. Also (similar to trying to pinpoint origination with "you gave me that cold"), it is realistically impossible to try to backtrace events to the beginning. You may trace results back to one event -- but that event has preceding things that led up to that event. At the beginning, it may depend on a butterfly's wings.

How does that affect the way to approach life, or business? It appears to conflict with the other advice of "don't sweat the small stuff" -- but it actually just amplifies upon a recognition that you really don't know what is the "small stuff" in advance of the future. A few examples from various aspects of life.

You are driving to work in a stream of vehicles. You allow someone to enter into the stream. That may prevent them from doing something dangerous later when they have reached their limit of patience. Or it may allow them to go through an intersection two minutes earlier and avoid an accident that takes place there. You cannot know in advance.

Pay it forward. Behavior within a car is one extra level of separation -- but what about just a smile and a greeting when you see someone you know? Or holding the door open for a stranger (or someone you know) that has their hands full? Some little things can multiply as one person's smile carries through to a second smile and a third.

A lot of small things can make one large thing. In business, creating a foundation that can survive changes and problems makes a huge difference. It is especially useful to allow for, and encourage, growth. If you succeed (which, of course, you hope you do) then retrofitting the needed base decisions and processes may hurt your results or even derail you. That foundation is composed of many "little" things -- vacation and benefit policies, ethics codes, decision processes, approval requirements, and so forth. At a size of 10 people, it is easy to just "wing it" but what happens if you grow to 100 people within a year? So busy and no time to hash out what should be happening.

One small thing can create a movement. One photo of a plastic straw harming a sea turtle cascaded into an awareness of the specific results of our behaviors and a move to turn back to biodegradable straws and lending support to more general desire to stop littering and polluting.

Small things can directly compound. Try saving your loose change each week and take it in to the bank at the end of the year. You will probably be very surprised at the total. Or, even more, set aside 5% of your salary each paycheck to put into some type of increasing account (money market, stock portfolio, 401(k), credit union savings) and see how it multiplies (at a greater or lesser rate depending on many different factors).

I occasionally (maybe too often) play a game called spider solitaire. During the first hand, there are usually multiple possible sequences to start things off -- and it matters a lot to the outcome. If you get stuck at the end, you replay and change the starting sequence. Playing one game, I had to redo it five times before I came across the best starting sequence -- and it was NOT a sequence that played the most cards the first round. Sometimes delaying taking profits at the beginning help to maximize your final achievements.

What is small to one person may be huge to another (or vice versa). This is another problem with categorizing things, in advance, as "big things" or "small stuff" -- there is no tool that "fits everyone".

Multiples of small things make a huge impact. I used to watch a program called "Unwrapped" -- which presented videos on how food items were processed. It gave a glimpse of the huge extrapolation from the home kitchen to a food that is eaten by many across the country. About 15 million "Snickers" candy bars are made each day. Think about how many tons of chocolate, sugar, and other ingredients are needed each day. Then think about how much in a year. Even in our small choices, when it is multiplied by a substantial part of almost 8 billion people, the small things can make a huge impact.

Saturday, September 22, 2018

Crazy Rich Richard Cory

People have always been fascinated by how the "rich" live their lives. From "Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous" to "Crazy Rich Asians" to "Sullivan's Travels" and more (look them up in IMDb or RottenTomatoes if you are not familiar with them), there is a huge appeal to the illusion of being able to peek into the lives of those who just don't seem to have a single financial care in their lives. Of course, there are many different levels of "rich" (and "poor", as discussed in others of my blogs).

There is one stage of "rich" that has to choose between various excesses -- not enough for all things without consideration. Another yacht or that huge diamond? A private jet or another 6,000 square feet in the mansion? At this stage, the operative word is "or". They have a lot more money than they need, and even have to work at spending it all, but they still know how much things cost to make choices. Although they may not know what a gallon of milk costs, it is very likely that they know how much they are spending on groceries per month (but the total percentage may be insignificant).

The penultimate stage is only a matter of "and" -- "or" is unnecessary. They don't know how much things cost because it doesn't matter. In a lot of cases, they don't even know how to pay for things because others do it for them; their activities, including purchases, just happen without their awareness of what happens in the background. This is particularly true for those from inherited wealth. These politicians, and other wealthy individuals, couples, and families are truly ignorant of the realities of life for the 98% of the population.

So, they should be happy, shouldn't they? As Paul Simon said in his song, Richard Cory, written in 1965 and recorded in the album, Sounds of Silence, by Simon and Garfunkel, it isn't quite so straight-forward:

When an individual, or group, no longer has any survival needs to satisfy, they have to find, or create, anchors to reality. This can be seen by the situation of many famous artists who are catapulted into riches and fame and end up killing themselves via unregulated excesses. I cannot speak to the mind of Paul Simon about how he envisaged the person behind Richard Cory but it is apparent that Richard Cory did not have sufficient reasons to keep going.

When the great imbalance in income inequality occurred prior to, and precipitated, the Great Depression, many suicides occurred because they did not know how to function as merely "rich" (losing 90% of $100 million still leaves $10 million).

Some people create anchors that are not particularly healthy -- and which have the danger of being accomplished and no longer sufficient. This includes greater and greater accumulation (of wealth, property, power, ...) which never satisfies and is, at heart, an addiction -- treating the economic system as a game in which they want to come out as "winners" (and create the most "losers"). Sometimes it is internal political intrigue such as happened with the Medicis of Florence (now part of Italy). Many times an income overflow includes visible excesses.

Healthier options attempt awareness of the lives, and needs, of the rest of the population. This may be anchored via religious, or spiritual, beliefs. It may be from an intellectual recognition of needs and realities. Or it may arise from a conscience which realizes that their fortunes are based solely on the efforts, and labors, of others.

No matter the basis of the anchor, it is needed to redistribute the excess in order to stay healthy. Foundations, charities, donations, university chairs, inheritance taxes, properly progressive tax structures, and increasing employee wages and benefits to living wages are all part of the pool of methods to relieve the pressures that build up with income inequality and concentration.

There is one stage of "rich" that has to choose between various excesses -- not enough for all things without consideration. Another yacht or that huge diamond? A private jet or another 6,000 square feet in the mansion? At this stage, the operative word is "or". They have a lot more money than they need, and even have to work at spending it all, but they still know how much things cost to make choices. Although they may not know what a gallon of milk costs, it is very likely that they know how much they are spending on groceries per month (but the total percentage may be insignificant).

The penultimate stage is only a matter of "and" -- "or" is unnecessary. They don't know how much things cost because it doesn't matter. In a lot of cases, they don't even know how to pay for things because others do it for them; their activities, including purchases, just happen without their awareness of what happens in the background. This is particularly true for those from inherited wealth. These politicians, and other wealthy individuals, couples, and families are truly ignorant of the realities of life for the 98% of the population.

So, they should be happy, shouldn't they? As Paul Simon said in his song, Richard Cory, written in 1965 and recorded in the album, Sounds of Silence, by Simon and Garfunkel, it isn't quite so straight-forward:

They say that Richard Cory owns one half of this whole town,

With political connections to spread his wealth around.

Born into society, a banker's only child,

He had everything a man could want: power, grace, and style.

.

With political connections to spread his wealth around.

Born into society, a banker's only child,

He had everything a man could want: power, grace, and style.

.

.

.

He freely gave to charity, he had the common touch,

And they were grateful for his patronage and thanked him very much,

So my mind was filled with wonder when the evening headlines read:

"Richard Cory went home last night and put a bullet through his head."

He freely gave to charity, he had the common touch,

And they were grateful for his patronage and thanked him very much,

So my mind was filled with wonder when the evening headlines read:

"Richard Cory went home last night and put a bullet through his head."

When an individual, or group, no longer has any survival needs to satisfy, they have to find, or create, anchors to reality. This can be seen by the situation of many famous artists who are catapulted into riches and fame and end up killing themselves via unregulated excesses. I cannot speak to the mind of Paul Simon about how he envisaged the person behind Richard Cory but it is apparent that Richard Cory did not have sufficient reasons to keep going.

When the great imbalance in income inequality occurred prior to, and precipitated, the Great Depression, many suicides occurred because they did not know how to function as merely "rich" (losing 90% of $100 million still leaves $10 million).

Some people create anchors that are not particularly healthy -- and which have the danger of being accomplished and no longer sufficient. This includes greater and greater accumulation (of wealth, property, power, ...) which never satisfies and is, at heart, an addiction -- treating the economic system as a game in which they want to come out as "winners" (and create the most "losers"). Sometimes it is internal political intrigue such as happened with the Medicis of Florence (now part of Italy). Many times an income overflow includes visible excesses.

Healthier options attempt awareness of the lives, and needs, of the rest of the population. This may be anchored via religious, or spiritual, beliefs. It may be from an intellectual recognition of needs and realities. Or it may arise from a conscience which realizes that their fortunes are based solely on the efforts, and labors, of others.

No matter the basis of the anchor, it is needed to redistribute the excess in order to stay healthy. Foundations, charities, donations, university chairs, inheritance taxes, properly progressive tax structures, and increasing employee wages and benefits to living wages are all part of the pool of methods to relieve the pressures that build up with income inequality and concentration.

Saturday, September 1, 2018

The math of gerrymandering -- how, why, and where

Lots of news articles on the topic of gerrymandering of late -- mostly about political bias and court decisions. But just what is gerrymandering and how does it work? The word was created as a merging of the name of Governor Gerry of Massachusetts and the word salamander -- due to an artist's perception of the way the electoral districts were created (from Wikipedia).

Gerrymandering is the process of creating boundaries such that one group has the advantage over another group. It is particularly used if the process gives a minority group control over the majority group.

Districting occurs to divide up larger areas into smaller areas. For federal government in the U.S., it is a result of the Constitution and the periodic census. For the House of Representatives, the number of representatives per state shifts depending on population as reflected by the census. Within that state, districts are created that have approximately the same number of people within each district so that each person can have an "equal representation" compared to others in the state. For state and local districting, the rules can vary from that although the principle of "equal representation" is a common ground rule.

Note that the representation of the Senate in the U.S. does not follow this general formula. With a fixed number of Senators per state, less populous states have greater representation per person. This was done deliberately to make sure that states had equal say in certain legislation. It carries over into the Electoral College of the U.S., with less populous states having a greater proportional say than the more populous states (although the total numbers are still greater for the more populous states).

How does it work? Let's say that we have a state divided into 100 districts (I think of it as a 10 by 10 grid). Each box/district has 100 people in it. Thus, there are a total of 10,000 people in the state (10 x 10 x 100).

Assume that group A makes up 65% (6,500 people) within the state. Group B makes up 35% (3,500 people, there may well be more than two groups but let's keep it simple).

One method of districting would put 65 people from group A and 35 people from group A in each district. If this is done then, within each district, group A has democratic control (assuming equal voting by each group -- not often the case in real life). Group B has very little direct control.

Another method would put 100 people from group A in each of 65 districts and 100 people from group B in each of the remaining 35 districts. This allows for proportional representation within the state or federal level but, locally, each group would have a monopoly within its district.

However, if we put 100 people of group A in each of 35 districts (3,500 people -- leaving 3,000 people) and distribute the rest of group A equally among the remaining 65 districts, we would have approximately (not quite exactly) 46 (3000 / 65) people from group A in each of those 65 districts. Group B would have about 54% of the population in each of those 65 districts. Thus, group A would control 35 districts (35% of the state/federal vote) and group B would control 65 districts (65% of the state/federal vote). The power of the minority is flipped with that of the majority. This is the situation that is often the focus of the term gerrymandering.

Sometimes, as in the case of Maryland, the term gerrymander is used in shifting of the voters -- according to percentage of registered voters, Party B should have 3 out of 10 representatives; it has 1.

There is a limit beyond which gerrymandering is not possible. For example, if 90% of the state were in group A, it would still be possible to keep the 90% representation by putting all of group A in 90 districts but it would be impossible to distribute them such that group B would take over control.

Often, the controlling group determines how the districts are divided. Thus, once gerrymandering has occurred, it is easy to maintain control by the controlling group (even if they are the minority group) unless the total percentage of group A grows enough to preclude gerrymandering by group B (they can try, but it won't work). This is the situation that has been, and probably will continue to be, presented before the higher courts.

It is fairly easy to determine if the minority is overriding the majority but fair districting is difficult to do to allow proportional state/federal representation and still have local (within the district) non-monopolies of the dominant group in that district.

One solution would be to dissolve artificial grouping (George Washington hated the concept of political parties) but that is not very likely to happen.

Although it is usually not called gerrymandering, the same process occurs in the division of a metropolitan area into school districts. The school districts COULD be created such that each district has the same tax revenue base -- ensuring that the schools within each district have the same amount of money to spend per student as in other districts. That is not often the case and the result is school districts with a higher amount per student and other districts with a lower amount per student. This could be avoided by spreading the revenue distribution over the entire metropolitan area rather than per district -- but that is often considered "unfair" by those in wealthier districts.

Saturday, August 25, 2018

A level playing field -- the desirability of regulations.

I am a firm believer that MOST companies want to be a good neighbor. They want to have fair and equitable wages and benefits for everyone. They want to do their share in the local economy so that they give as much, or more, than they take. They want to leave the world in as good of, or better, condition than how they found it. They want to produce safe products than are of benefit to people. The guiding forces of those companies want their children, neighbors, and communities to be proud of them, what they do, and how they do it.

Alas, within the business world, what is desired is not always what can be done. This is especially true for public corporations which are in the public eye and which are often constrained to a short-term view to the next quarter's earnings. A company must be competitive if they want to continue to enable jobs, give dividends and earnings to stockholders, and continue to grow, innovate, and produce.

When I was growing up, we had a large lumber and pulp mill as the primary economic force for the town. To the best of my knowledge, they produced high quality goods and treated their employees reasonably well. But one day I neglected to wipe off my glasses immediately after a brief shower. Later in the day, when I was cleaning them, I found that the rain had etched permanent spots in the lenses. The rain was highly acidic. Some of my friends, who had houses much closer to the mill, knew that they would have to paint their entire house at least once a year because the paint would not last longer than that. The town just considered it as part of the side effects of the company but I doubt that anyone, within or without of the company, truly liked or wanted the acid rain.

Sometimes, doing things, that seem to be more costly, prove to be cost-effective in the long run. Thus, after examination and real-life testing, up front costs sometimes prove to be long-term savings. One example of this is a well-known bulk goods company that has a higher-than-average salary structure as well as better benefits than the general industry. Many would think that this would put them at a competitive disadvantage. However, the long-term result of this has been shown to be higher productivity, much less turnover of staff (which is very costly), and a more welcoming atmosphere for the ongoing customer stream. And all of that saves money and makes the company more competitive and profitable.

In other cases, doing right cannot save money -- it costs money. One company that dumps all of their wastes directly into the local river or lake will have lower costs than a company which minimizes their wastes and treats remaining wastes such that they do not damage the environment. Unless the environmentally friendly company has other areas in which they are more efficient, they will not be competitive against the toxic company. (Note that the process of minimizing wastes often saves money -- but requires initial investment of time, effort, and money.)

And this is where regulations come into play. If all the companies have the same positive requirements in place then meeting those requirements does not affect the competitive landscape of the business. All the companies can (and are indeed forced to) do the "right" thing without putting themselves into a poor competitive position.

The regulations, in themselves, have a net neutral effect on companies' profits and cost of doing business. However, the monitoring and enforcement of those regulations do have a cost and sometimes that is a significant cost. This is the "burden of regulations" that is often discussed in political arenas and in public and social media. It is real and it can hit small businesses harder than large businesses because the gross amount is similar for the small and the large business such that, as a percentage of invested profit, it hits the small business much harder. In other words, if I make $100 profit, and I must use $35 to fulfill the needs of regulations, it will hit me much harder than a company that makes $100,000 profit and must use $5,000 to fulfill the needs of regulations.

Regulations create a level playing field and are usually of benefit to everyone -- within and without of the company. We need to determine methods to keep that level playing field and that means ways to minimize, or distribute, the costs of monitoring and enforcement.

Saturday, August 18, 2018

It comes as a bundle -- one cannot pick and choose

I love broadleaved deciduous trees and forests. I love the way they provide wonderful shade in the summer and the way the leaves vanish to let the sun through in the winter. I love the rustling sound they make in the wind and the slow unique shapes that they don throughout the course of their lives. Note that I have nothing against coniferous trees -- I just happen to love deciduous trees.

However, for broadleaved deciduous trees to thrive, they do best with humidity -- particularly "cold-deciduous" trees for which leaves are lost due to cold -- and I strongly dislike humidity. The areas where they gather tend to reinforce their own region of higher humidity due to their higher transpiration rates.

I grew up in a high humidity area -- without air conditioning -- and not-very-fondly remember flipping my pillow and myself on top of the bed in the night attempting to feel cool enough to sleep. But there were lots of deciduous trees all around with their beginning slender trunks and their older, uniquely shaped, trunks and profiles. They were the trees with which I grew up. Later in my life I moved to drier climates and, although I did enjoy the lack of humidity, I missed all of the wonderful leafy trees. So, in order to have what I love, I also have to have what I don't like so much.

I enjoy food. But too many calories, too much sugar or fat, or unbalanced nutrition is not good for me. So, I have to notice what, and how much, I eat. It isn't always easy and it is very tempting, especially in modern U.S. society, to get what is easily available, inexpensive, and not necessarily the best for me. So, I cannot just eat what I love -- I have to balance it with conscious decisions. I won't say that it is BAD to have to make those conscious decisions -- they are probably very good but they are part of the bundle.

In order to work in a job, you have to be able to get to the job and back. I interviewed for one job in a town and the work seemed very interesting and the co-workers pleasant and intelligent. But the commute would have been 75 minutes of heavy traffic each direction (2 1/2 hours per day). All part of the bundle.

A more complex situation is where a person finds a job that they love but it doesn't pay enough to maintain current familial expectations of living circumstances. Change your schools, housing, and general budget or find a different job that does not appeal as much but can support your current living situation?

Do you love the ocean? Do you want to live near a beach? Well, it will either cost more than away from the beach or you will have less living space and closer neighbors. Or on a mountain side with a view of the city? The more people who want a location, the more other things one needs to accept as a consequence (more money, less space, ...). It all comes as a bundle.

Do you want to have a bodybuilder's physique? Be prepared to do a lot of things -- specific and regular exercises, revised and strict diet, possibly even shaving the body if you want to enter competitions. You just cannot have the one thing without having to do all the others.

How about relationships? Is everything exactly as you would like it -- ever? If so, hearty congratulations.

There are lots of things that are possible in the world but few are isolated from other things -- and we have to take them as a bundle.

Saturday, August 11, 2018

Can everything be faked? Digital editing and manipulated data

Spoiler alert -- once upon a time (in 1993) a murder mystery movie was released called "Rising Sun". Part of the evidence was a digital video of an area which presumably was the time/space where a murder took place. It turned out that the digital video was edited (but not quite carefully enough) to fake the evidence.

In 1993 (25 years ago as of the writing of this blog), this was relatively new to ponder. We knew that photos could be doctored/changed/altered but, in this movie, a central point was that digital video could also be changed. (Once changed digitally, film copies could be made if desired.) Twenty-five years ago, this took a lot of time and many computers. Doing such a thing still requires a lot of processing power but that power is now available on many home computers (or even phones or tablets).

We are seeing this capability ad nauseum within the social media. Within less than 24 hours, a new set of memes, photos, and sometimes videos are released purporting to prove something or call something out. Some are real. Sometimes it is obvious (quotes from Lincoln about the Internet SHOULD be immediately recognized as fake although I have found that a lot of people tend to believe them) but often it is not. Sometime the source is a public satire, or irony, site and "should" be recognized as such by those that read them -- but they often aren't. This happens on all segments of the political spectrum.

An awful lot (too much) of the time, a forgery is only discovered to have taken place by recreating how the fake was created (such as finding the original photos that have been merged together).

The foundation problem is that if it CAN be faked, how does one determine the primary reality for this particular universe? For articles and "news" segments, it is possible to research multiple sources, find a general agreement from various sources and determine with a high probability (but not 100%) what the reality is. What does one do about forged supporting documents? It is not easy, but it is possible, to find component parts from various photos, videos, sound recordings, and such to be reasonably sure that something has been compiled together, and manipulated, into a different item -- a "photoshopped" photo, an edited sound recording, and so forth.

However, we are reaching the point of being able to synthesize (or create) from scratch whatever we want. Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI) has gotten so good that, for films, they sometimes deliberately make it appear less real because people can be annoyed if they think it is "real" when it isn't; they like to know it is CGI. That objection doesn't apply when the person, or group, creating the artifact WANTS to have it be accepted as real.

As per previous blogs, this doesn't just apply to distorting current things of interest -- it can also be applied to faking history and re-inventing the past. Nor (as per other previous blogs) can we rely on memory to be sure. There are those who do not remember what was said by a politician the previous day.

So, to attempt to answer the question posed in the subject -- can everything be faked? Probably so. As is true that social change falls behind that of technological changes, our ability to create fake items is overwhelming our ability to prove that it has been done. What methods of verification do you use? What can be done to more easily separate the close-to-true from the false? Is this just a new reality that we need to accept and learn to deal with?

Saturday, August 4, 2018

Life and work -- a closed energy cycle

Recently, Jeff Bezos, of Amazon founding fame, gave an interview in which he stated that he did not believe in the idea of "work-life balance". He prefers to view it from a holistic point of view where each gives energy to the other. A more complete link to the interview, and his perspective, can be found here.

Whether one considers it to be something to "balance" or whether it is to be considered a "holistic" exchange of energies, it is still an aspect of how life, work, and "play" is viewed. It is not the same for everyone. One potential definition of "work" is the set of things that you must do in order to support the necessities of life. One potential definition of "play" is that which you do because you enjoy it. And "life" is a combination of the time that is spent in work, play, and the other moments of your days, weeks, months, and years. So, work and play are subsets within the grouping called "life".

The huge variety occurs (and creates the apparent dichotomy of Jeff Bezos' view on the "balance") because many people think of work and play (and life) as disjoint activities while others (like Jeff Bezos) feel that work and play can largely overlap -- you can greatly enjoy the things you do that provide for the necessities in life with only a minor part spent doing things you actually do not like.

I have never read any poll results that indicate what percentage of people love almost all of their time at their work -- and I have considerable doubts that a valid poll could be conducted. But, we can probably agree that not all people love their work almost all of the time.

For those people, like Jeff Bezos, who love everything they do at work, there really isn't any need to find any "balance" between work, play, and the rest of life. But, for those who are not in that category, there is a set of energy available and it needs to come out at least neutral or, preferably, positive.

Everyone who does not have society supporting them (either through inherited wealth or via social subsidization programs), does need to have work -- based on the above definition of work being what is needed to be able to live. If you love your work but cannot stand what happens to you after work, then you need more work hours to give you the ability to cope with outside-of-work. If you do not love your work then you may need more time available outside-of-work in order to have the energy to do a good job while at work.

This comes back full circle to the question of "how does one achieve a healthy work-life balance" (for those who do not love almost all of their work activities)? The place where you work very much wants, and needs, you to be productive while you are working. You cannot be productive if you are draining your batteries on a continuous basis.

There are many methods used to help to promote the ability to work productively. These include flexible hours, shortened work hours or condensed work weeks, part or full-time remote work, provision of ergonomic furniture, career training opportunities at work, clubs, bonuses, recognition awards, and many, many other methods. What works for one person may not work for another person. We are each unique.

The work environment can be adjusted to become a "better" place to work; it can change to require less energy or even, possibly, generate more positive energy. This is a combination of what your work organization can do and what you do for yourself to make work a positive place for you. Another approach is to do more of what you love during your off-work hours -- to generate that extra energy needed to pull you through the work days. What will not work -- for the business in which you work or for yourself -- is to keep putting in more and more time doing things that take away your energy. It may not be necessary to find your "bliss" but it is necessary to save energy to do the things that make your life enjoyable and, if that IS your work, then that is wonderful.

In the long run, finding that "balance" is an ongoing journey of life.

Saturday, July 21, 2018

Survival of the Fittest? Really?

"Survival of the fittest." This is a phrase that is used by various people at various times. But what does it really mean? According to the Merriam-Webster online dictionary, the most appropriate definition for "fit" is "adapted to the environment so as to be capable of surviving". So, we would assume that "fittest" would mean that a person was BEST adapted.

One huge problem with looking up definitions is that the definition makes use of other words which have their own definitions. In this case, we have the word "surviving" used in ADDITION to the word "survival" within the original phrase. So, it appears that "survival" is redundant -- the "fittest" would automatically survive since that is part of the definition. But people like redundancy (particularly with acronyms -- WAN network, for example) so that's OK.

We still have three major descriptive words in the above definition: adapted, environment, capable. I won't keep pulling in definitions from the dictionary because eventually they tend to cycle. Definitions end up based on the connections between words and experiences. We learn what "green" really means by correlating between a perceived color and the name. We learn what "a building" means by having someone (parent, teacher, friend, ...) tell us which constructed objects are considered to be a building. And so on.

But a big part of the word "adapted" is that it implies change. That indicates that the bird, butterfly, human, tree, or whatever may not have originally been easily capable of surviving. Note that the change may, or may not, have occurred within a single entity's lifetime. The adaptation may have taken place over generations -- with the best of each generation creating just a little bit better (a new best) for the next generation. This is close to the original Darwinian usage of the phrase.

However, it is possible for change to occur within a lifetime. This relates to another key word within the definition -- "capable". In the case of a tree or a bird, they are capable (have "attributes required for accomplishment") of survival at that time or not. They cannot learn to put on a coat, or build a house, or develop a medicine, or whatever. They survive or they die based on their existing capabilities and instincts -- with the big factor being whether they can survive long enough to create that next generation that may be able to survive better or longer. Other animals may have some degree of ability to adapt to become capable such as a raccoon learning to use a stone to open a clam.

Humans are remarkable in their ability to change (if they want or are forced to do such). They can fabricate devices, think up strategies, and make triage decisions based on what they believe is needed for survival. And, bringing in the last of the three key words, they can do it based upon the current (or projected) environment.

Which brings us back to the word "fittest". Humans are well suited for adapting and for being capable of survival. But just how they need to adapt and of what they need to be capable depends fully on their environment. An environment can mean a physical environment. For cold, people can make and wear warm clothing, build a shelter, collect and use fuel, and so forth. For severe heat, the problems are more complex but it can be managed. Living undersea would require other adaptations and so forth. In each environment, certain physical attributes would be of inherent use but the greatest area of capability to adapt is the access to, and ability to use, materials to be able to adapt, and survive, within the physical environment.

For humans, environment for the "fittest" is more often a social context. This can be split into general society or within a business/industry/subsection of the society.

The smartest person may be the "fittest" within a academic world. However, depending on the political environment of the academic setting, the ability to manipulate managerial opinion may be of greater value -- leading to a situation where the smartest is NOT the "fittest". Most of us have lived through the complex environment of a high school (or secondary education role). Being the "fittest" is a combination of many different attributes and it is likely there will not be consensus within the entire school. One sub-group may consider one member the "fittest" while a different sub-group, with different characteristics, considers a different person the "fittest".

One potential definition for civilization is a society having rules and methods of enforcing those rules. This divides up the social environment into two rough groups. The first group has the rules, and benefit of enforcing the rules, defined by an individual. The second group has the rules, and benefits of enforcing the rules defined by the members of the group (in a pure democracy) or a subset of the members of the group (many other political/economic models).

The first group can be described as a "Mad Max" type of post-Apocalyptic world or a "cave person" type of pre-settled world which stabilizes when the "fittest" person emerges in the group. The "fittest" individual is often the person who is the most ruthless; the most willing to do whatever they want, or need, to do to get what they want. There can be delegated authority but it exists only to support the ruling individual. If the members of the group do not unify to alter the situation, it can expand to larger numbers of people under a dictator (or absolute monarch or emperor).

It is a type of "fittest" that many would hate because "there can be only one". There are members of groups of people, who romanticize the survival of the fittest, that think that THEY will be that ONE "fittest" out of the many in the group -- but each of the hundreds, thousands, or millions think that and only one will really be that.

I like the second group. I am one of the many who welcome the rules and enforcement created, and enforced, by the group. I am unlikely to ever be THE "fittest" but I can attempt to be one of the many "fittest". It is a type of environment in which I can strive to adapt to survive and still allow others to attempt to be their own "fittest". Such an environment exists only because groups of individuals can create enforcement of rules. Thus, people cannot murder. People cannot steal. People cannot do things to harm the group. And so forth.

Groups of people create rules and enforcement of rules to benefit the group -- which can be a neighborhood, city, state, country, or planet. The group membership delineates those who are expected to follow the rules and benefit from the enforcement of the rules. Change in group composition can cause fear and anger within some in the group because it can change the number, and choices, of the various "fittest" subgroups and individuals (and, thus, a previous "fittest" (or privileged) person or subgroup may lose that status -- or the exclusivity of their benefits).

Friday, July 13, 2018

Real Estate Inflation -- an income wedge

Investing in real estate is not always a sure bet -- the "bubble" in the U.S. in 2008 is a recent indication of a "correction" when real estate prices were rising much faster than demand would normally expect -- and when people were going beyond the point where they could truly afford to buy real estate. But, in general, real estate prices continue to rise.

This is something very pleasant for the real estate owner. Over the long run, the value of the land or property (a "parcel") is expected to rise. In the short run, it may be difficult to sell. It is not "liquid" -- it can only be exchanged for money or other value if someone else happens to want it. But, if it is a good piece of land or property, it will probably find a buyer at a good price.

What defines a "good price"? What are the components of the rise in value of land or property? Realtors are likely to say the phrase "location, location, location". That is actually only half of the criterion -- the other half is "distinctive". By building high or covering a wide area, the specific location can be widened and a specific property or land area becomes less valuable. However, with increasing density and encroaching natural borders (such as hillsides or rivers) or supportive resources (water, power, sewage, ...), there is a limit to the number of parcels that can be available at the same approximate location. Each, of course, will have their own view and orientation which may make them more, or less, valuable.

Another component of the price can be quality. A well-built, or designed, home should be of greater price. If the person/company that designed, or built, it is well known (Frank Lloyd Wright?) then that automatically adds to the price. History can add to the price -- if Abraham Lincoln slept there then the price should go up (assuming it can be proven).

Yet another aspect of pricing is determined by the general income level of the neighborhood. There will be a lower limit of reasonable pricing determined by the cost of materials (not applicable in the case of land) and local labor -- but that lower price limit may be voided in cases of desperation or foreclosure. However, the price will float upwards as the prices of the parcels around are rising (for whatever reason) as competition between realtors, owners, and buyers start to change the lack of sufficient property into higher prices

All of these parts of determining value are indicative of why housing prices vary -- more expensive in some locations and less expensive in other areas. A 2,000 square foot house in San Jose, California will cost a lot more than a 2,000 square foot house in Mobile, Alabama. (Even though the quality of the house will probably be less in San Jose.) Within Wichita, Kansas, a 2,000 square foot house in a wealthy neighborhood will cost more than that within a lower income neighborhood (although neither will come close to the price of a house in San Jose).

Once upon a time (when I was growing up -- not quite the dark ages), my architectural drafting instructor told us about an expected ratio of land to square footage of a house. As I recall, the "footprint" (the amount of land the foundation required) of a house was supposed to be no more than 1/9 of the lot size (land). (It was never indicated as to any rule-of-thumb on apartments or townhouses.) With a reduced expectation, and use, of land -- as well as an increased percentage of the total price spent on land -- it is now not unusual to have a house occupy 1/3 of the lot (sometimes even less in urban areas).

In addition to the house occupying more of the lot, there is incentive for the builder to increase the size of the actual house. Houses are listed, and compared, by $xxxx/square foot (in other areas Money/square meter). The price to build is NOT the same for all sections of a house. Kitchens and restrooms are more expensive. By adding more square footage to the "living" areas, builders can squeeze out more profit without increasing the price per square unit of area.

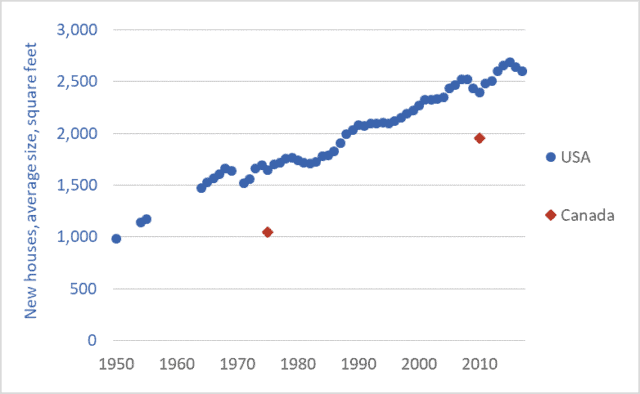

A chart of this increase in house size can be seen from Darrin Qualman's post.

Perhaps this is not particularly egalitarian -- people who have more income (or more inherited wealth) can buy larger houses in more desirable locations with better views, schools, climates, landscaping, local attractions and such than those who are poorer. But such has been the case since land and property started "belonging" to people and is likely to continue.

The greater problem is having the AVERAGE housing price go up faster than the AVERAGE wage. As time goes on, a smaller and smaller percentage of the population can afford to buy housing. This also reflects upon the situation for renting since renting is the process of fostering out to others property that has been purchased by someone. In other words, rents are loosely based on the amounts of mortgages for the property.

Before I started researching to double-check facts for this blog, I thought that real estate prices were rising much faster than inflation. It does not appear to be the case. Even wages are reasonably stagnant (decreasing only a small amount, on average, against inflation) from amhill.net's post (you may find other sections of the post of interest, also).

But, since house prices are per square foot and the average size of a newly built house has increased by 250%, many fewer people can afford a house. What they can afford is an apartment (or maybe a townhouse) which shifts the size back to that of a house built in the 1950s. That may not be that unreasonable -- the increased size is a factor of literal "inflation" but it does mean that the "American dream" of a stand-alone house with its own yard is more and more out of reach for many people.

One new trend against this flow is for that of the "tiny house" movement. Note that, although the square footage is quite a bit smaller than the typical newly built house of current days, the price per square unit of area actually goes up (once again, the cost of kitchen/bathroom is more expensive and there is less "living area" to offset that cost). Of course, people can still buy their own lots and have their own "moderate house" built. It just doesn't seem to be currently popular -- which means that it may prove hard to sell in the future.

In summary, part of the lack of ability for people to afford housing is an illusion. Since the size of houses has increased (and the prices accordingly) and wages have remained stagnant then fewer people can buy the houses currently being built. However, if the size of the living area is kept constant -- and the form of the living space is allowed to change from that of a "dream house and yard" -- then people's ability to afford housing has not changed. Unfortunately, the numbers of housing units built of an affordable size is not keeping pace with the percentages who can afford them -- causing housing and rental shortages.

Tuesday, July 3, 2018

Why Do Prohibitions Fail -- the reduction of undesired behaviors

In January of 1919, the United States passed the 18th Amendment to the Constitution and, a year later, it went into effect. This Amendment prohibited the "manufacture, sale, and transportation" of drinking alcohol. Note that it did not prohibit the drinking of alcohol but, legally, the only alcohol a person could drink was from the stockpiles that were already in their possession. Although there was initially a drop in alcohol-associated problems such as driving under the influence and arrests for drunkenness, difficulties started to increasingly plague the movement. Enforcement was very difficult -- easier in rural and "pro-temperance" areas and harder in urban settings -- and there were increased costs both in policing as well as prisons. In addition, the now-illegal activities of "manufacture, sale, and transportation" increased both the price of drinking alcohol and the attractiveness of criminal (by definition, those participating in illegal activities are criminal) participation in "bootlegging". Al Capone was a very famous leader of such gang activity.

By February of 1933, the Amendment was increasingly unpopular. The high price of bootleg liquor and alcohol primarily punished the middle and lower income people (remember that drinking was still legal). The reduction in tax revenue was a problem within the period of the Great Depression. The "temperance" (those who favored alcohol suppression) movement was being taken over by people whose primary motivation was their interpretation of religious documents. Police and government corruption and organized crime and violence was getting worse daily. AND, there was no success in the overall reduction in drinking alcohol by the general populace. Prohibition had failed. Upon the 21st Amendment being introduced in February, it was quickly ratified and became law on December 5, 1933 upon the signature of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

In summary, the prohibition of drinking alcohol failed -- and failed badly. It did not achieve its primary purpose (reduction in drinking). In fact, the continued (now illegal) activity caused huge problems in police and government corruption, organized crime and violence,and general disregard of the law.

Drinking alcohol is not a "victimless" activity. Overuse of alcohol causes problems for the individual as well as their family and other people who care about them. The effects of alcohol cause reduction in judgment and focus which, in combination with certain environments (such as driving), can cause "side-effect" problems such as accidents, fights, and job loss. Yet, it was emphatically proven that prohibition did not, and does not, work to reduce misuse.

With such a dramatic, and relatively recent, knowledge of the failure of prohibition it would be reasonable to think that we would no longer try prohibition. Yet, that would be clearly incorrect. Among the many activities that have been, or currently are, prohibited include:

- Drinking alcohol

- Gambling

- Drugs currently categorized as illegal

- Socially disapproved sexual activity (adultery, masturbation, prostitution, pornography, public exhibition, ...)

Note also that the "harm" may be defined from a religious or societal basis and not from a measurable physical change. Thus, there may not be consensus -- nor may such attitudes be constant -- on what is of "harm" to people or to society. I am certain that there are other items that some people would add to the above list. I am equally certain that some people would remove some items.

Recognizing that there is not full agreement as to what is of "harm" to an individual -- what can be done to reduce those behaviors? Both the experiment of Prohibition (focused on alcohol) and many other prohibitions (focused on other items, including the items on the above list), have shown -- over and over -- that prohibition of "vices" DOES NOT WORK. In fact, it is counter-productive in that reduction is minimal and the continued illegal activity increases crime and corruption with net loss in available tax money for more productive uses.

Successful reduction of disapproved activities fall generally into two closely related categories -- education and expansion of alternate choices. Often, a third item is added -- regulation and oversight -- in order to keep track of the activities as well as to provide social recompense (tax revenue, for example) that is not involved in reduction of the activity.

Education provides a mechanism to inform people of the effects of the activity. This is usually focused on the negative effects (there is little desire to increase the perception of positive effects

In order for there to be a choice, there must be more than one option. It is neccesary to provide OTHER, preferred, activities in which they can participate. If no other choice is available then the single, non-approved, choice is still the "best" choice for a person. Provide attractive alternatives!

Saturday, June 23, 2018

Why Write a Blog -- why write anything at all?

My official view count on blogspot recently exceeded 20,000 views. I am fairly certain that this is a low number. There are places where I post my blog that make their own copy and, thus, the official counter is not incremented. Twenty thousand is not really that amazing. There are people who are better well known, who work much harder at getting their blogs visible, who blog in association with a company or technology, and others in different circumstances who have view counts that make mine insignificant. But, it is significant to me.

This total of 20,000 views is from a long history. I have been working on this set of blogs for almost 11 years and have written 115 blogs. They total around 100,000 words -- which is about the same as a couple of moderate-sized novels. A guesstimate is that it has taken about 450 hours or 11 full-time workweeks (or an average of one 40-hour week per year).

Why put in this amount of effort? I have occasionally joked -- sometimes more than half seriously -- that I write because I am a masochist. I have gaps of weeks to a month or so when I just cannot get myself to go back to the keyboard. There are often few, or no, comments -- "what is the sound made by one hand clapping?". In some social media, it is not uncommon for people only to comment, or downvote, if they don't like it -- and generate only silence if they like it or are OK with it.

I have even had one moderator of a social media site insist that blogs were the same as spam. Upon suggesting that she, or he, read it -- they, in proud fashion, insisted that "they didn't read spam". The reality that their arguments would apply equally to any posted article (Computerworld, Newsweek, Time, Washington Post, ...) made no impact on their worldview.

The question as to "why bother" applies to most writers. The statistics of about 10 years ago were that 90% of all writers do not, or cannot, make a living at writing. I suspect that the statistics have not changed much -- possibly it has even gotten worse as there are many more "markets" where a person can publicly write for free. I am sure that there do exist blog writers who make a living -- maybe in the same general percentage as other writers. Personally, I would have loved to have made reasonable money from my blogs -- but I haven't.

When I wrote, and had published, my three technical books, I earned back my royalty advances which placed me in the top 20% of all non-fiction writers; I didn't earn very much past those advances. I may have earned a dollar an hour for those books (they are all long out of print). My initial fiction book has earned closer to a nickel an hour -- though I always have hopes that the right person will read it and it will take the world by storm (it has been well reviewed). I think that writers, in general, have to have an optimistic core or they just wouldn't write.

So far, this blog has listed lots of reasons NOT to write. Don't expect (you are allowed to hope) to earn money writing. You are more likely to hear complaints than compliments. You may even have to justify your very existence in your writing.

So, why write? I have been in the paid workforce for about 47 years -- working in the computer science arena for 40. During that period of time, I have read thousands of books, worked on hundreds of projects, interacted with thousands of people, worked in dozens of different roles and even in a dozen different fields (donut baker, programmer, wheat field tractor driver, company startup co-founder, small item construction field worker, manager, ...)

In this, I am certainly not unique. There are many of you out there who have had as many experiences and some who have had more experiences or experiences that may be of more popular interest. A lot of you are like me -- wanting to share back with the community from which we learned and have gotten so much.

But, I like to write and am pretty good with the written word. So, as I fill up with experiences I want to share them -- and I can best share them via the written word. So, I write. And, among other methods of publishing, I blog.

Saturday, June 9, 2018

You Can't Give If No One Will Receive : a closed cycle of sharing

Most (but not all) of us were taught, as we were growing up, that it is good to give to others. Some societies include sayings such as "it is better to give than receive". The lesson sticks with people better, or worse, with a lot of the adhesive depending on what those who are close to us actually DO ("lip service" doesn't work well as an example).

Giving has no expectations of return. I give you a gift -- you may, or may not, give me back a gift. And that's OK. I give you a gift and you give it to someone else, exchange it, or I find it in the trash can at some later date; once I have transferred something to you then it is yours. That's OK also.

It's OK but it's not ideal. Ideally, you give someone something they want and like (perhaps even need) -- such that they will not WANT to discard it but will treasure it (or, in the case of something transient as in food or money, the memory of it) as a type of bond between the two of you. For this to happen, the act of giving can no longer be unilateral. There must be an active receiver in addition to the giver. I give, you receive. In the 1990s, a group called "The Boomers" had a song called "The Art of Living" which talked about this situation.

Many people are taught that they should give. Not a lot of people are taught that they need to receive -- and, certainly, not how they should receive. In the U.S., we have a lot of good givers (not always from as pure of motive as desired) but not a lot of good receivers.

OK. We get lessons on how to be a good giver (not that everyone does such). Give without thought of return, including not having conditions attached to the gift. Give according to what is needed, or desired, rather than what one most wants to give. Give as you can -- but not more than what is comfortable such that you will resent it.

What about that receiver side? There aren't many lessons on it. First thing is to recognize that receivers make givers possible. If you truly believe that giving is a good thing, then you need to learn how to be a good receiver. You don't need anything? Not even a compliment (which, if sincerely given, may be even better to receive than a material fortune)? Congratulations. Maybe you know someone else who does need what is being offered -- pass it along to that person, or group, giving credit to the person or group from whom it was originally given.

You do need something? OK -- you have joined the ranks of the majority. If something is freely offered to you, the first thing is to NOT feel guilty for accepting it. You are providing an opportunity for them to give. But do be appreciative as they did not have to give. My relatives always told me to write a thank-you note but I still don't see any reason for such if you have already thanked them in person. But do thank them. What if you don't need it, want it, and don't know of anyone else who does need or want it? That is more awkward as they may have indeed felt that it was a generous offer on their part. Express appreciation and then suggest a more appropriate recipient. Let them know they have done something good and you want it to be used to the best extent possible.

What if someone insists on "giving" you something even though you have insisted that you don't want it? Well, that is not really giving. I am not sure there is a specific word for it in English but it is more related to assault or forcing than giving. I cannot say what the "giver" feels under such circumstances but the one being forced to take something is not going to feel good about it. Of course, "receiving" something without a corresponding giver is just taking (perhaps stealing).

Let's work towards the ideal of truly giving, with a full and joyous heart, and receiving, with appreciation and acknowledgement of self-worth. In a world where life is not often "fair", we can help to even things out.

Saturday, June 2, 2018

Is "free" ever free? -- a matter of choice and perception

"Buy One Get One Free!" This is a famous advertising slogan within the U.S. Often it is shortened to just BOGO. Do they really give you one "free"? Of course not -- try asking for just the free one. They will respond with a laugh if they are in a good mood. Financially, it means they are selling the product for half price (50% discount) but -- from a consumer/shelf rotation point of view -- it is not quite that. By requiring you to buy two in order to get the discount, they are also increasing their sales volume. This is the non-food version of supersizing -- the food version of which I expand upon in my blog on "supersizing".

This advertising method is also used for other percentages and other quantities. Buy Two Get Three Free (60% discount with five products sold). No matter what the actual proportions, it is a method of advertising and tricking the brain into thinking that something is "free". Another variant is to have a "sale" offering 10 of product G at D% off. Or, in a specific example, if the article usually sells at $1 the offer is to sell 10 for $6. Sometimes, the advertising also says "must buy 10" -- sometimes it doesn't -- but, a lot of the time, people will still feel the urge to buy a full 10. (Read the entire sales quote including the smaller print.)

Of course, this type of "free" doesn't have to be within the same merchandise. "Buy Product X and, for a limited time, we will toss in Item Y (which we haven't been able to sell on its own) FREE." This has the big advantage of reducing inventory on Item Y. This is not saying that Item Y is not a good item -- but it doesn't have the appeal necessary to sell it by itself at a good profit margin. Product X gets a boost in sales attractiveness without directly discounting its price.

In the above cases, the primary economic advantage is selling more products. In the U.S., and in most of the larger countries, consumerism is a heavy factor in the economies of the country. From this orientation towards consumerism, many factors are emphasized within society. These include expanding feature sets, obsoleted -- and "new" future fashions, minimal useful worklife, and so on. In the past decade, a transition has started being made from physical to electronic products -- higher profit margins and less required capital with an ecological benefit. However, this causes labor redistribution and retraining ("no free lunch"

"There is no such thing as a free lunch!" Absolutely true -- but it may be absorbed into another existing budget -- this can either be within a corporate advertising budget or within a system of taxation. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, it can also apply to benefits in one area requiring extra effort or pain in another.

My wife and I often get calls of the nature: "you are the winner of a free vacation to our wonderful resort in Paradise, Country X". We are of a certain age that is expected to be looking towards retirement. We "won" because they have determined (from extensive data mining and other methods) that we can potentially afford something and that we have a reasonable chance of actually buying it. They may have also researched a "soft touch" factor on us (how well do we resist sales techniques). At any rate, we are part of a group of "winners" and, statistically, they are likely to get more profit/sales out of the group than it will cost up-front to get us all to their resort and pay for the advertised benefits.

This isn't saying anything bad about the resort -- it may be fantastic and it might even be something for which we might be grateful for the opportunity to purchase. But it is an example of how something "free" is incorporated into a larger budgetary item -- in this case, advertising.