With the new tax "reform" in the United States in the news, the topic of income inequality resurfaces as something of interest. As will have been noticed, the way that the economy actually works is something that I find continuously fascinating. As for income inequality, just what is it? How does it begin? How does it accelerate or become less?

[Please note that the numbers used within this blog are snapshots and may be different in a different year's snapshot.]

In the first place, there are two different inequalities within a capitalistic economy -- income inequality and wealth inequality. These are often discussed as if they were the same thing. While it is true that there is often a correlation they are not the same. Income inequality is the difference in the amount of usable income in a given period (usually a year) between different income divisions (see my blog about income groups if you are interested). Wealth inequality is the total control of capital associated with a particular division. Generally, wealth inequality is even worse than income inequality because wealth both accumulates and compounds (wealth generates more wealth).

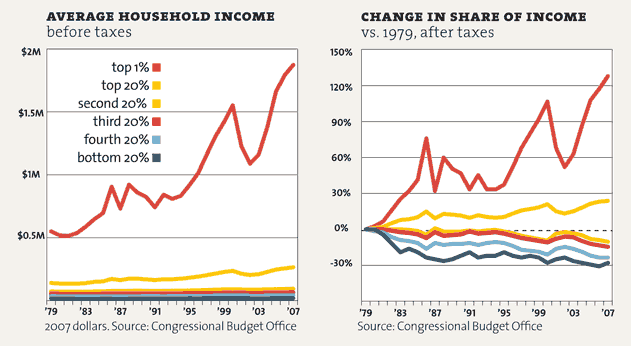

If we look at the following graph of income inequality in the United States:

First note that these graphs only continue up until 2007. The general trends have continued through the present year. Next, note that the increase is much higher with the top 1% than the next 19%. The bottom 80% actually indicate a DECREASE in income.

Income inequality arises out of the difference between income and required outgo. For the lowest income groups, the amount of income is less than the required spending. This deficit is dealt with by supplements from the general tax pool and by dropping budget items that are not immediate for the family -- dental care, general medical care, and so forth. Eventually income rises to the point where the income matches what is required for spending for essentials.

We have now reached the bottom of "middle income". This continues until there is extra income beyond essentials. This is the point at which there is actually a voluntary potential of the family being able to accumulate additional wealth. In other words, there is an amount of money that has discretionary spending possible. It could be put into savings, or invested in stocks and bonds -- or it can be spent on more expensive cars, long vacations, fancy clothes, and so forth. In the first situation, the family has the potential of raising their overall wealth (and income). This is the historic "rags to riches" story -- but it requires having enough income to have excess and the number of people in this category continues to shrink and, for better or worse, an expensive car often wins out over extra savings.

Finally, we hit that upper income category. This is where both survival and initial spendable extra income have been exceeded. It has to be either hoarded or invested. This is complete "gravy" and has nothing to be done with except to expand it. This is where the tax laws can be written to help the vast majority who generate the income or to help those who already have more than they need.

There is no "trickle down" -- no lower levels that make 1/4 or 1/3 of what the higher level employer makes (and then continuing on down with the next level making, perhaps, 1/8 or 1/6 of the highest level). Only a "splash over" occurs -- lots of service people employed to do things that those with excess income do not want to do themselves. (Of course, the service people are still grateful to have income.)

So there is the summary. Those who don't have enough to survive and must be helped, those who do have enough to survive but are faced with choices on spending and often spend the additional income beyond survival, and the third category with excess that has no choice but to keep growing unless compensated for with tax laws that re-distribute the money back to the people who generate it.

Beyond fairness, however, there are reasons why it is very dangerous to allow working capital to be concentrated in the hands of a small percentage. First, the rich are not particularly different from the poor (except where nutritional situations have caused permanent damage) -- they have a "normal" distribution of intelligence from not very to average to very smart. If the top 0.1% of the population (about 160,000 families in 2015) families in the United States have control of 22% of the nation's wealth (2015 statistics) -- that means that 80,000 families of below average intelligence are controlling 11% of the nation's wealth. Even more, the top 10% (16 million families) control 78% of the nation's wealth -- giving us 8 million families of below average intelligence controlling 39% of the nation's wealth. In other words, there is a lot of economic power concentrated in the hands of people who have no particular special quality about knowing how to make use of it.

The second part of the danger is that, with 16 million families (out of approx. 160 million) controlling 78% of the nation's wealth, we have a situation of a capital circulation problem. If 160 million have the capacity to equally spend on goods and services, the capital flows freely. If it is concentrated in the hands of a few, it is more parallel to a tourniquet being applied to part of the body.

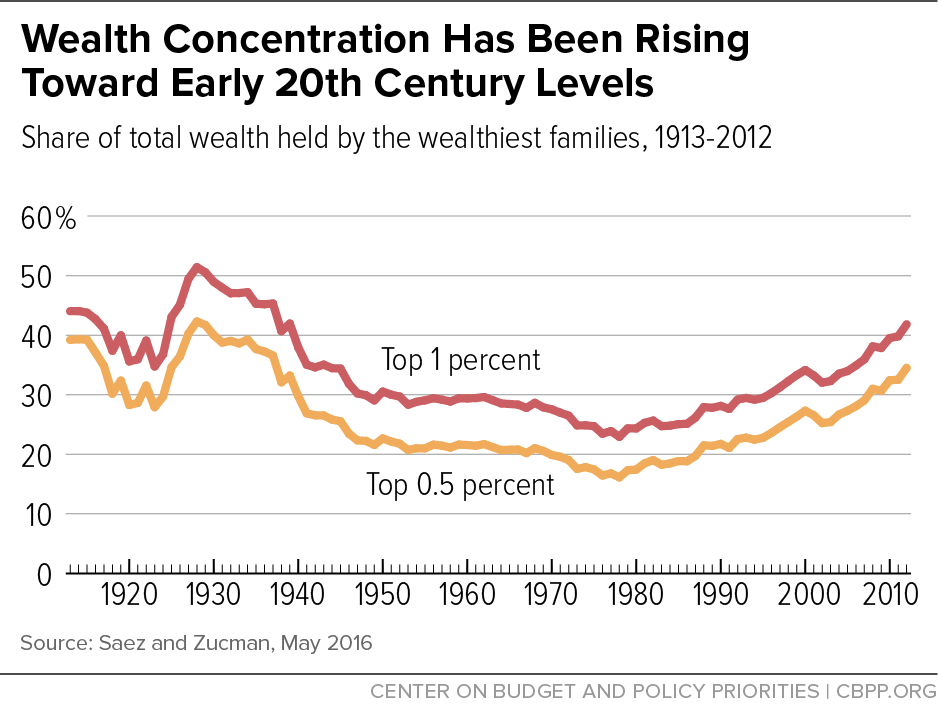

We have a continued concentration of wealth in the hands of a few and the recent tax "reform" act will accelerate this concentration. We have two major demonstrations of this situation (I do not claim ONLY two demonstrations) -- the Great Depression and the French Revolution. Both were situations where income got overly concentrated in the hands of the wealthy.

We have now surpassed the point in history of the end of the 1920s and are rapidly heading to the point in 1929 where someone, who had a lot of capital and power in his (or her) hands made a mistake and started the dominos falling.

Will this happen again? I don't know but we have few documented cases where income concentration exceeded these levels and a stable society continued. These cases were demonstrated primarily in pre-colonial Europe and an outlet existed (unfortunately for the existing native populations of Australia and the Americas) for the poor and desperate. Where is that outlet -- that safety valve -- now?

No comments:

Post a Comment